Contents

This is a series of occasional blog articles about my practical experience of, and feelings around, actually retiring (well, partially retiring), and bringing some of my pensions into payment.

Introduction

Part 1 – From WEFT to WARP (Aug 2025)

Part 2 – I retired on my phone! (Aug 2025)

Part 3 – Getting paid your pensions (Sep 2025)

Part 4 – A Darlington diversion (Sep 2025)

Part 5 – Two centuries of parallels (coming Jan 2026)

BLANK

Introduction

At school, we’re educated as a group, with classmates.

And most of us work in groups too, with colleagues.

But we retire alone.

There’s no word (like classmate or colleague) to describe the people around us who we observe as retirees, and from whom we can learn.

For this third, and hopefully most wonderful, stage of life, there’s no widespread practice of sharing handy tips (in the way there is in classrooms and workplaces).

So increasingly, people are telling their own retirement stories as a way to try and help others.

For example:

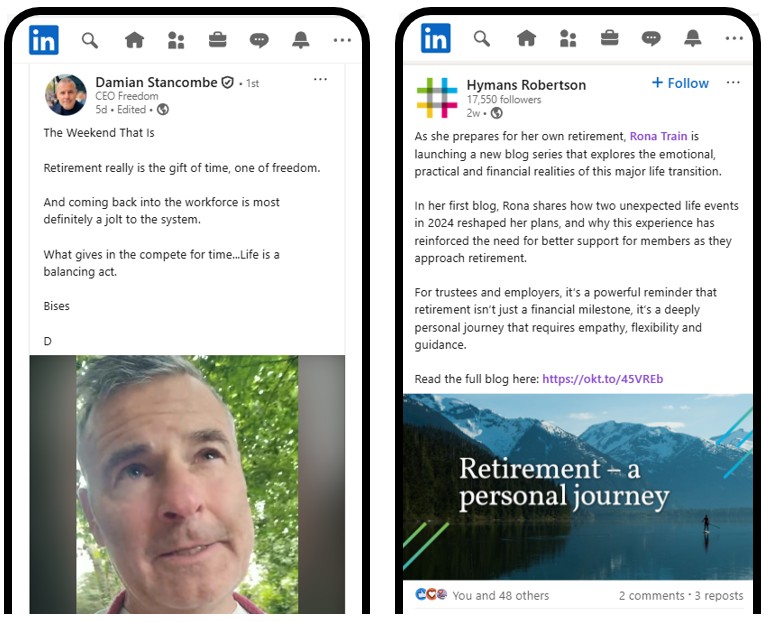

- Former Barnett Waddingham Partner Damian Stancombe, now CEO of Freedom, is well known for vlogging about his retirement, and his subsequent return to the workplace, and

white space - Hymans Robertson Partner Rona Train blogged and podcasted about her own retirement experience in the Summer of 2025.

white space

There’s great power in the telling of real stories, I think.

So I thought I’d tell my own story, probably in several Parts. Let’s see how it goes – I’d love your feedback.

Thanks ever so much for reading. If you’d like to chew over anything here, please do get in touch – thanks.

Cheers, Richard.

RS, Summer 2025

BLANK

BLANK

Part 1 – From WEFT to WARP (8 August 2025)

The weaving concept of weft and warp has often been used in literature and art as an analogy for the dichotomies of the world, and our lives in that world.

The expression is also sometimes used to depict the underlying structure upon which something is built, as in the “fabric” of life.

As recently as July 2025, on the new album from the wonderful trance group Above & Beyond, in the lovely title track Bigger Than All Of Us, Justine Suissa sings:

“we are the weft and the warp

in this universal tapestry”

So what’s my weft and warp analogy?

Well, l want to go further and turn them into acronyms.

I’m turning 58 in August 2025. Getting old now.

And whilst I don’t want to stop work quite yet, I would like more flexibility over how I use my time.

I’m very lucky to have four deferred Defined Benefit (DB) pensions (built up in the 1980s and 1990s). I previously wrote about them in my Dashboards Nine-Nine series of articles in Pensions Expert.

To start receiving a monthly income from these DB pensions, I’m going to ask my schemes to bring them into payment.

These will hopefully just about cover my core monthly outgoings – you know: bills, council tax, food shop, etc..

It’s going to be tight – I’ll talk more about economising in later Parts of the story.

So I also want to continue with some part-time work contracts, particularly as there’s so much more yet to be done to realise the many benefits of pensions dashboards for millions of UK consumers.

Therefore, from August 2025, I’m going to be Working And Receiving Pension – I’m going to WARP!

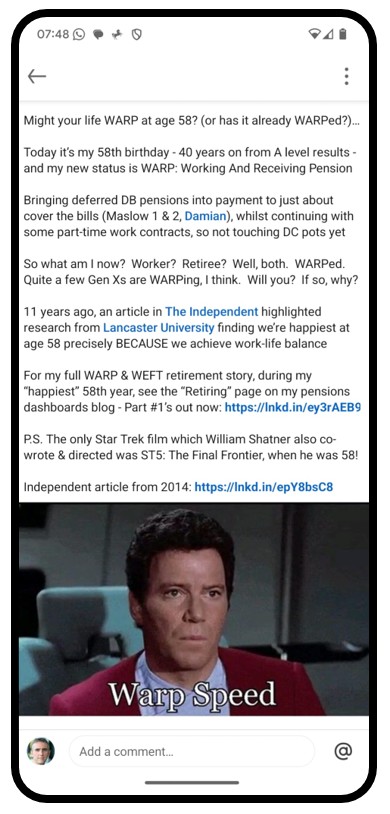

Here’s my LinkedIn Post all about this idea:

The 2014 article from The Independent I referred to highlighted research done at Lancaster University.

The academics found it’s the good work-life balance which 58-year-olds (like me) are able to strike that makes them the happiest of all UK age groups.

So that’s what I hope WARPing will do for me too. I recognise I am extremely lucky to be able to do this.

But hang on. If, in my world at least, to WARP is to be Working And Receiving Pension, then what is to WEFT?

Well I guess you could say to WEFT is to be Working Enthusiastically Full Time.

(And I guess if you’re Working Anxiously Full Time, you’re just WAFTing.)

If (for whatever reason) you’re no longer able to WEFT, maybe it’s time to think about WARPing? (if you can).

There’s another analogy I really like. Thanks to Online Clothing Study (OCS) for the image below depicting the direction of WEFT and WARP in woven fabric.

Perhaps the left and right of WEFTing (Working Enthusiastically Full Time) could be seen as the daily commute to and from work? Really important activity, but very steady, and potentially wearying over time.

Whereas WARPing (Working And Receiving Pension), whilst not completely leaving that back and forth world, enables you to break free to an extent, into new worlds and new adventures, stretching forward into the future with hope and excitement.

In this way, I see the two states of i) full time working and ii) part time working / retired, not as two opposites, but rather as two complementary, linked notions.

A bit fanciful – but maybe you get the gist.

In subsequent Parts of my retirement story, I hope to talk about the practical experience of being paid a pension, and how it feels to live life as a WARPee.

In future Parts, I may even talk about the experience of bringing my defined contribution (DC) pensions into payment. Once we have dashboards, default guided retirement, target supported, AI bots, who knows what? I’ll start small, though, with just my DB pensions.

But before concluding this introductory Part 1, I wanted to say a little about why I’m no longer WEFTing. Have I lost enthusiasm? What happened? What’s the story?

My WEFT history, and my gratitude to four IFLs

In truth, I haven’t been WEFTing (Working Enthusiatically Full Time) for 11 years, since 2014.

I hope my Work has been Enthusiastic during my Full Time pensions career – but that’s for others to judge.

What I do know, is I’ve been helped enormously, in particular by 4 inspirational female leaders (IFLs) at 4 different workplaces, who all took a chance on me.

If the below reads a bit like a retirement speech, then that’s cos it is, I guess. I am retiring after all (sort of).

White space

1980s – IFL #1 Caroline Gray: I dropped out of uni at 18 in 1986, with neither the intelligence nor the application to complete a music degree. After two odd, but important, jobs as a porter at Wokingham Hospital and a Sales Assistant at WH Smiths in Wokingham, my pensions career started in 1987 when I was 20.

Caroline recruited me and several others to Heathpens, part of the CE Heath Group (which, long after I left, became NorthgateArinso, and then eventually Capita).

We were customising the Unipension admin system for major in-house scheme clients. But as well as schooling me in pensions, Caroline taught me a great work ethic and focus, for which I’ve been grateful my whole career.

I then moved down the road in Reading to Prudential, working on their mainframe pensions system for Paul Moss then Stewart Waight, and then transferring to pensions administration under Paula Gibbons.

Stewart really encouraged me to complete my PMI APMI exams from 1992 to 94, and Paula helped me really cement my understanding of what pensions admin is.

White space

1990s – IFL #2 Heather McGuire: I wanted to move in-house, though, and a role came up to be in charge of the systems at the in-house team running the AA Staff and Management Pension Schemes in Basingstoke.

Again, I was very fortunate that Heather recruited me and really developed my confidence, not just in pension systems but in different aspects of leadership too.

That confidence was necessary. Not long after I joined The AA in 1999, it was bought by Centrica, and the pensions function in Basingstoke was outsourced to Aon in Farnborough, with all staff being TUPE’d.

At Aon, I was lucky to pick up a couple of national admin roles, but my heart was in-house, or at least supporting in-house schemes.

So, I was incredibly lucky to be recruited by Pete Sparshott to the specialist PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) Pensions Management Consulting (PMC) practice. I believe the confidence instilled in me by Heather at The AA made me a better PwC Consultant.

White space

2000s – IFL #3 Helen Dean: During my 11 years at PwC, from 2003 to 14, I was incredibly lucky to work on major on site engagements with the pensions, or benefits, functions at RBS, RHM, ING, DfE and the NHS.

But my longest client engagement, from 2007 to 10, was with the Personal Accounts Delivery Authority (PADA), predecessor of the National Employment Savings Trust.

In Newcastle, Helen appointed me as part of a PwC team to support the programme management of implementing the automatic enrolment policy. Helen subsequently retained me, now at PADA down in London, to help with the development of the Nest Scheme Order and Rules – see my About page for more.

If Caroline at Heathpens built my confidence, and Heather at The AA developed it, then working with Helen at PADA really took it to another level. Helen is such an inspirational leader, as many who have subsequently worked with her as Nest CEO have said.

I remain enormously grateful to Helen, and Caroline and Heather, and all the other colleagues mentioned (and not mentioned) above for all their support and encouragement over the years.

So what happened? Why did WEFTing end, Richard?

Readers who know me will be aware my gorgeous wife Heather Wood (another Heather), who I met at Prudential, was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2004 shortly after our third child was born. She had chemotherapy for 10 years but sadly died when the cancer metastasised in 2014.

I spoke about this recently on The Silent Why podcast:

Two years earlier, in 2012, PwC had been really kind and allowed me to transfer from London to their Reading office, under Peter Woods, so I could be closer to home.

But after Heather died, I just didn’t feel able to continue my full time client-focused work at PwC, at the same time as learning to be a single dad of three children.

So I left PwC (who had been tremendously supportive throughout Heather’s illness and decline). Luckily, I was able to do this as Heather had life assurance, so there was some money to live on. My top tip for all parents:

GET LIFE ASSURANCE – it’s a godsend!

Returning to work

After doing a fairly major project on the house in 2015, I thought I should get back to some form of employment.

But how best to do that, balancing with my new main role as a single parent?

Another stroke of luck: inspirational female leader #4

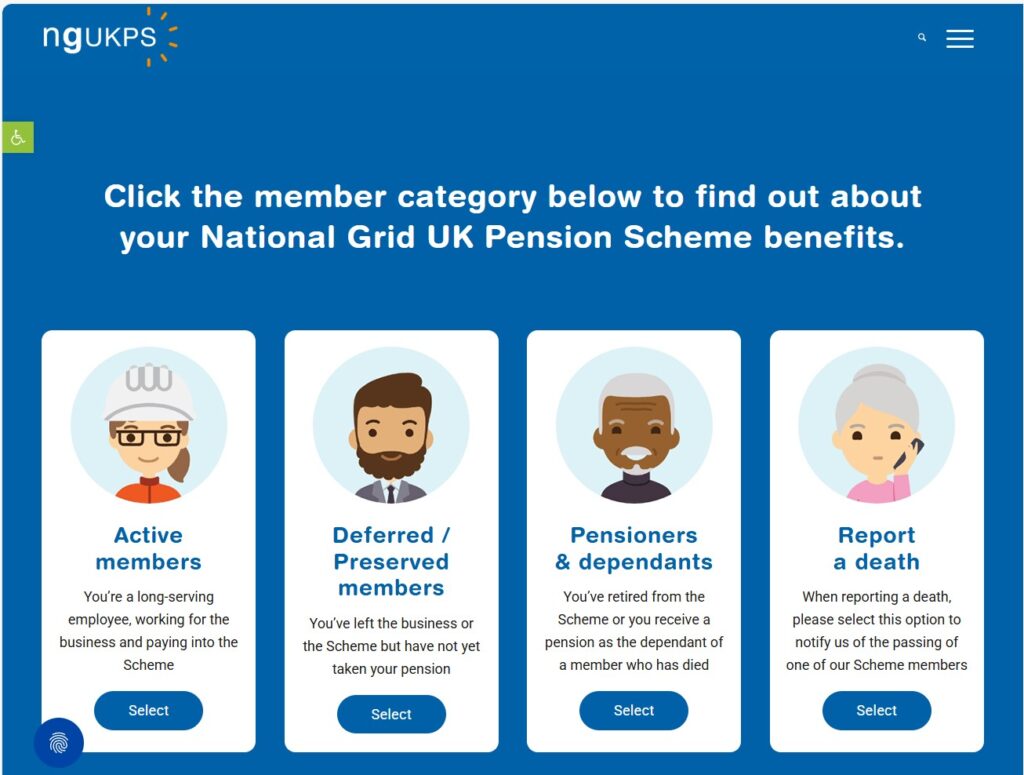

2010s – IFL #4 Julie Aspinall: 10 minutes through the woods from my house in Wokingham is the amazing Electricity National Control Centre (ENCC) for the UK – scroll down that link for a great video with Guy Martin.

At the time, in 2016, the National Grid UK Pension Scheme was run from some office space in the ENCC building and they needed maternity cover for their Operations and Governance Pensions Manager role.

I hadn’t done trustee support work before, but Julie took a chance on me and gave me the contract, for which I’m enormously grateful. Julie said a lovely thing:

“Perhaps you were due a break, Richard.”

Crucially, this National Grid role gave me confidence to continue being a contractor, which has given me flexibility to balance with my family role.

So, ever since Heather died in 2014, rather than WEFTing, I have WEPT (Working Enthusiastically Part Time) – I have certainly wept a lot (ask my kids!).

I’ve been privileged to do numerous part-time contracts with Nest, the PPI, MaPS PDP, ITM (now Lumera), PLSA (now Pensions UK), and Moneyhub – all related to my main focus of pensions dashboards and data.

But the opportunity, and confidence, to deliver all this work came from Caroline, Heather (McG, not wife), Helen and Julie – thank you to you all very much indeed, and to all inspirational female leaders x

And finally, here is Heather wife – she’s still in my head all the time, and will continue to be so as I continue on, aged 58, into my new life of WARPing.

Thanks so much for reading to the end of Part 1.

BLANK

BLANK

Part 2 – I retired on my phone! (15 August 2025)

In this series of occasional blog articles, entitled “Retiring”, I’m describing my real experience of retiring (or rather, bringing some of my pensions into payment).

In Part 1, I talked about the concept of moving from:

Working Enthusiastically Full Time (WEFT), avoiding

Working Anxiously Full Time (WAFT), through

Working Enthusiastically Part Time (WEPT), then to

Working And Receiving Pension (WARP).

Now, shall we actually bring a pension into payment?

My first deferred Defined Benefit (DB) pension was built up from 1987 to 1990 during my time at Heathpens (see Inspirational Female Leader #1 in Part 1).

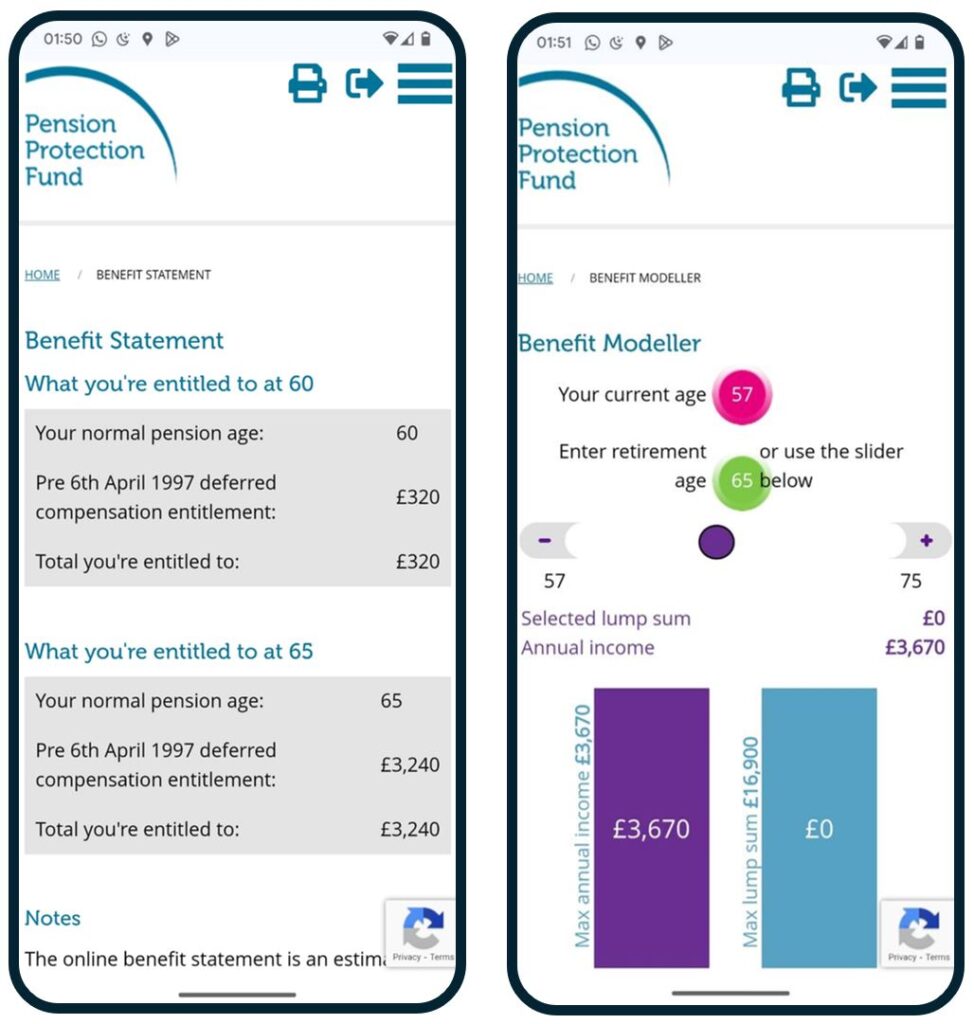

Unfortunately (or luckily, depending on how you look at things), the Heath Lambert Group Pension Scheme was transferred into the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) – I wrote about it in Episode #7 of 9 of the Dashboards Nine-Nine series of articles in Pensions Expert.

Bringing my PPF Compensation into payment, from my 58th birthday, was super easy.

I did it all on my phone in well under 10 minutes. Here’s a 2-minute video of the live process. And below are some reflections about how it made me feel.

Reflections

I found it incredibly exciting to bring my PPF Compensation into payment – hopefully some of that excitement comes across in the short video above.

Doing it made me think affectionately about the past, the present, and the future.

Past reflections

If you work at several organisations over your career, to which one are you most loyal at the end of it all?

I hope I was loyal to all of mine, at the time I was with them: Heathpens, then Prudential, The AA, Aon, PwC, followed by a variety of contracts over the last decade.

Getting hold of my PPF Compensation (originally accrued at Heathpens), put me in mind again of the lovely time I had there in the late 1980s, and brought back a heartfelt wave of gratitude I felt for the firm.

They were based in two large Bath Stone properties on the Kings Road in Reading – first, the middle one in the picture below, before moving to the one on the right.

38 years on, whenever I catch the bus from home into Reading, I pass these buildings and remember that special time.

I was a naïve, impressionable, 20-year-old, whose confidence had been knocked by dropping out of uni. Heathpens rebuilt that confidence, and I’m incredibly grateful for that to my former Heathpens colleagues and our legendary Fridays at The Fisherman’s Cottage!

And now, I’m grateful all over again, because those three years’ service (1987-90) are giving me a monthly income, and a lump sum.

Actually getting hold of your pensions, reminds you, viscerally, how you’ve spent your career.

Pensions are a fossil record of your working life.

Present reflections

35 years after leaving Heathpens, today in 2025, I found the PPF retirement process very smooth to operate.

The PPF announced the facility enabling members to retire completely online over three and a half years ago, in March 2022. This was during Oliver Morley‘s tenure as PPF Chief Executive.

The fully automated retirement facility reflected PPF’s lofty ambitions. As Oliver said in the PPF Strategic Plan video, also in March 2022, PPF’s strong foundation has:

“made us a role model in pensions and customer service … [ensuring] everything we do shows best practice in information, data and cyber security”.

This fills me with great hope for pensions dashboards, because Oliver is now, of course, Chief Executive of the Government’s Money & Pensions Service (MaPS).

Right now, in the summer of 2025, the team at MaPS responsible for the MoneyHelper Pensions Dashboard (MHPD) is starting to test it with real consumers.

If the MHPD is as smooth as PPF online retirements, then UK consumers are in for a treat!

Future reflections

Finally, thinking forward, I was massively struck by the PPF screen (quoted in the video above) which said I will receive £176 a month* for the rest of my life.

(*Actually, it’ll be more as it goes up each year.)

Obviously, this is what a pension is, right? A monthly income until you die. But I found actually seeing the words “for the rest of your life” very powerful indeed.

How long will that be? Who knows? As I explained in Part 1, my lovely wife Heather sadly only had 47 years. But my dad had more than double that. He died in 2018, just three weeks shy of his 95th birthday.

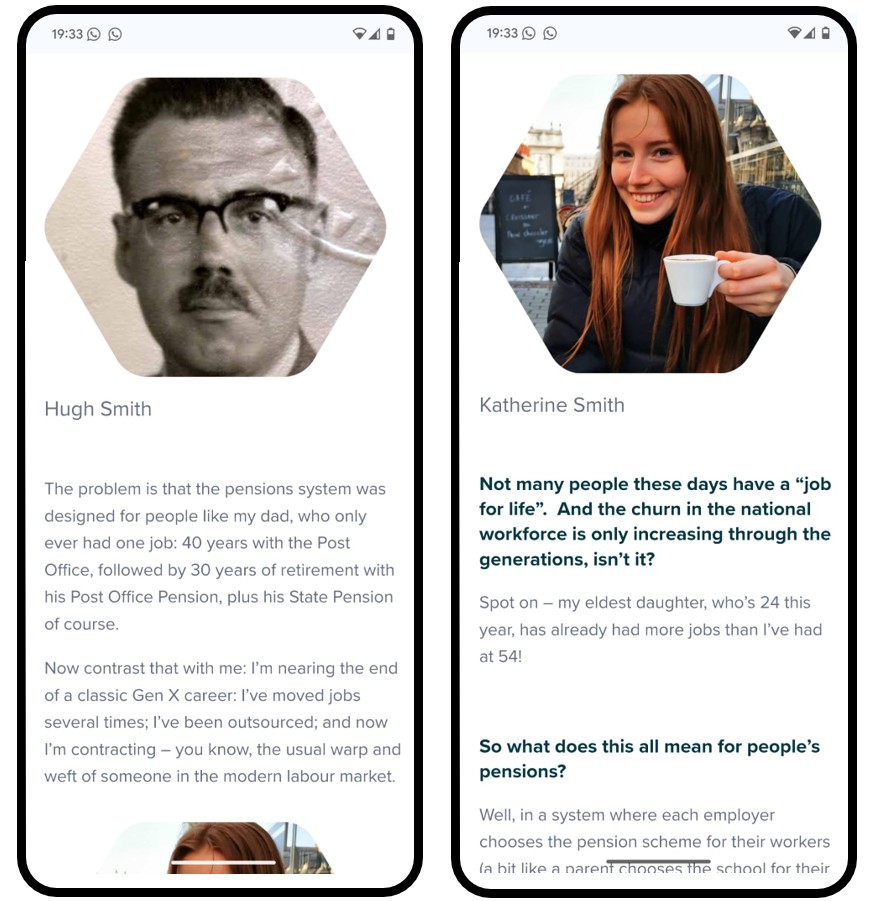

Three years ago, when I was contracting with Moneyhub, advising them on the build of their nascent Private Sector Pensions Dashboard (PSPD), I wrote a blog article which mentioned my dad’s career and pension (and my eldest daughter’s).

Hugh retired at age 58 in 1981, after 41 years’ service with Post Office Telecommunications. He then had 37 years of DB pension paid from the BT Pension Scheme.

If I live just one year longer than him, I’ll have 38 years of retirement, following my 38 years of working life.

There’s a lovely symmetry to that, I feel. (Although, as explained in Part 1, I’m not retiring, but WARPing.)

And, of course, I could die much earlier than my 96th birthday in 2063.

In the much nearer term future, though, I’m having lots of lovely ideas how I could spend (or invest) my tax free cash lump sum from the PPF. Anyone fancy a trip to The Fisherman’s Cottage to chew it over?

Thanks so much for reading.

In the next Part, I’ll talk about how it feels to be paid your pensions (to hopefully cover my core bills), whilst still doing some work contracts to pay for fun stuff.

BLANK

BLANK

Part 3 – Getting paid your pensions (1 Sep 2025)

Where’s the largest occupied castle in the world?

Well, according to the website of the British Royal family, it’s Windsor Castle.

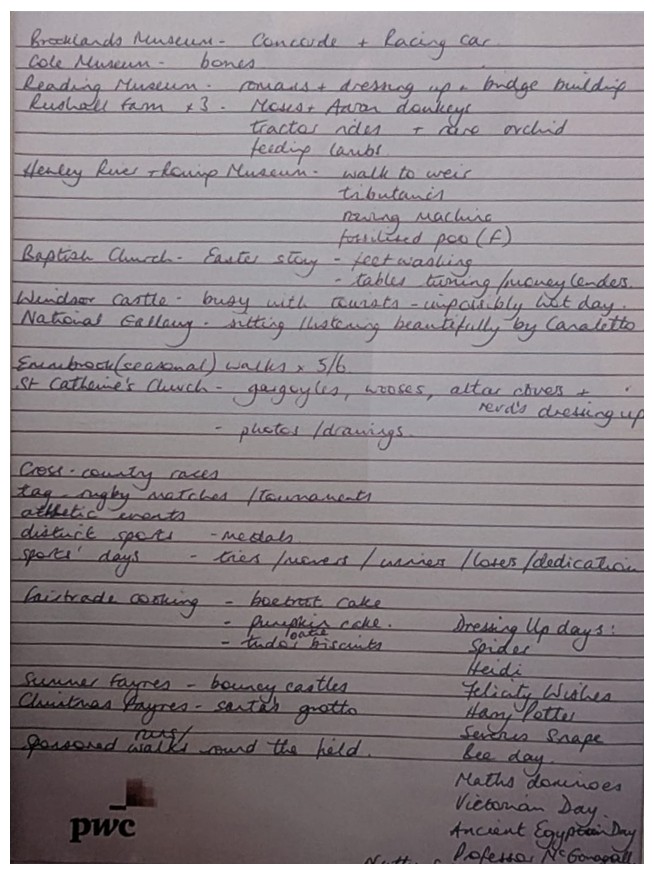

Being just 14 miles from where I live in Wokingham in Berkshire, the castle is a favourite destination for day trips from the primary school our children went to.

My wife Heather was a “mummy helper” on such trips.

I think she was quite effective at controlling groups of kids, so the staff often asked her back. She wrote a list of trips she went on (on a sheet of my PwC work paper):

Apparently, Windsor was “busy with tourists” and “impossibly hot”!

Anyway, because she was quite handy with schoolkids, she later became a lunchtime controller at the school, and then a backup Teaching Assistant (TA).

It meant she was enrolled into the Berkshire section of the Local Government Pension Scheme (LGPS)*, known as the Royal County of Berkshire Pension Fund (RCBPF).

In Berkshire, we’re kinda of proud of that “Royal” prefix: for example, the castle even appears on the member login page of the RCBPF website:

* Qualified teachers are enrolled into the Teachers’ Pension Scheme (TPS); other school staff into LGPS

Readers of this blog will already know that, after having chemotherapy for 10 years, very sadly Heather died in 2014, when our three kids were 15, 14 and 11.

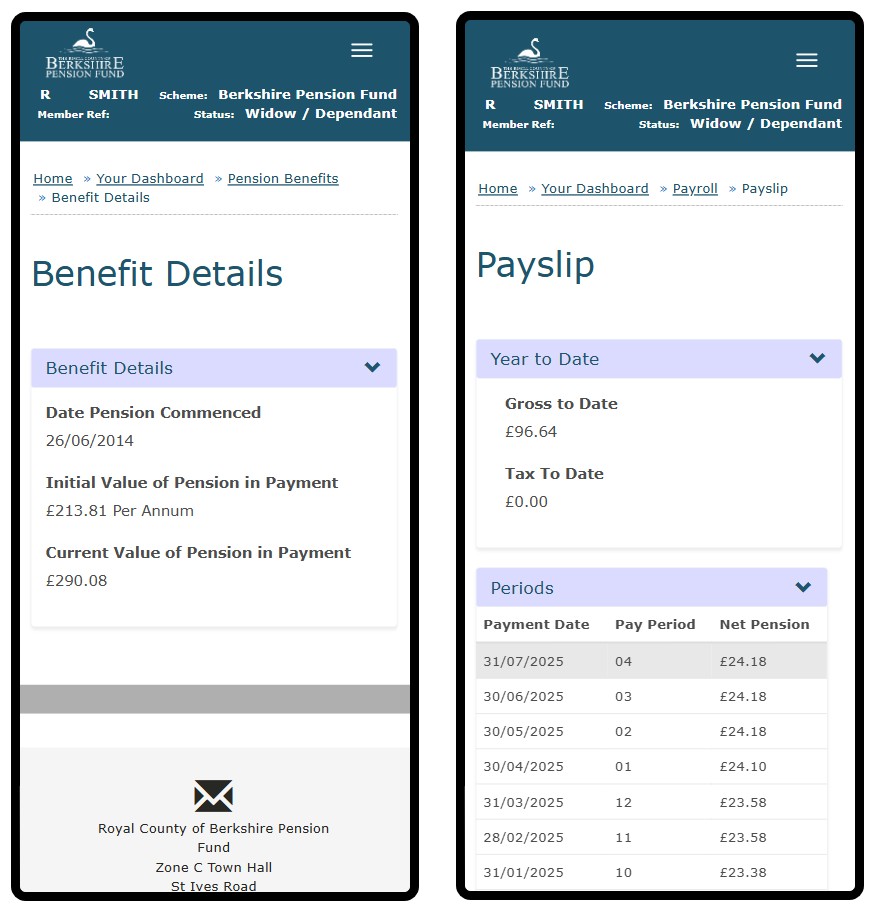

Because LGPS is a defined benefit (DB) pension scheme, ever since Heather’s death I have been lucky to receive an RCBPF Spouses Pension, every month since June 2014 and continuing until I die. Here it is:

Now, at £290 a year (or just over £24 a month), it’s hardly a king’s ransom (see what I did there?).

But I’d say three things about my RCBPF pension:

1. Every month, receiving that £24 into my current account is a wonderful reminder of my lovely wife’s commitment to our children and to our local primary school, all the time whilst she was living with cancer

2. I also receive a twice-yearly newsletter from RCBPF, called The Scribe, which again reminds me of the community Heather was, and I continue to be, part of:

3. Finally, notice (on the left-hand screenshot above) how the pension keeps pace with inflation: in the 11 years from 2014 to 2025, it’s gone up from £214 a year to £290 a year (an increase of 35½%).

A pension income which keeps pace with inflation is an incredibly valuable thing.

Suppose I live to see the 1,000th anniversary of the invasion by the King who built Windsor Castle (William I) – it’ll be 2066, 41 years from now, and I’ll be 99.

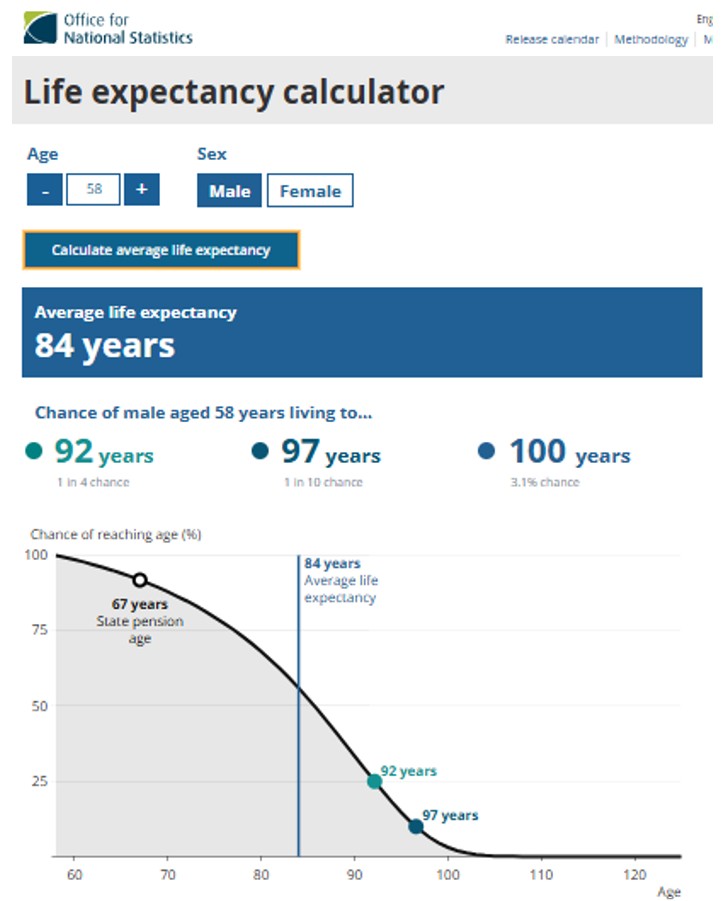

That might seem a little far-fetched, but there’s currently a 1 in 10 chance I could live to 97, according to the Life expectancy calculator on the ONS website:

So my RCBPF Spouses Pension will keep increasing, potentially for another 40 years, or more!

My other pensions

This whole blog is about me WARPing, i.e. Working And Receiving Pension (WARP), as explained in Part 1 above.

My idea is that my pensions in payment could cover my core bills (more or less), whilst I keep working, on some part time contracts hopefully, to pay for fun stuff.

Lovely though the £24 a month is from the RCBPF, it won’t even cover 10% of my monthly Council Tax bill.

So what other pensions have I got coming in?

Well, Heather was a part-time, and fairly low paid, TA at our local school, but the work fitted in well with childcare as well as having regular cancer treatments.

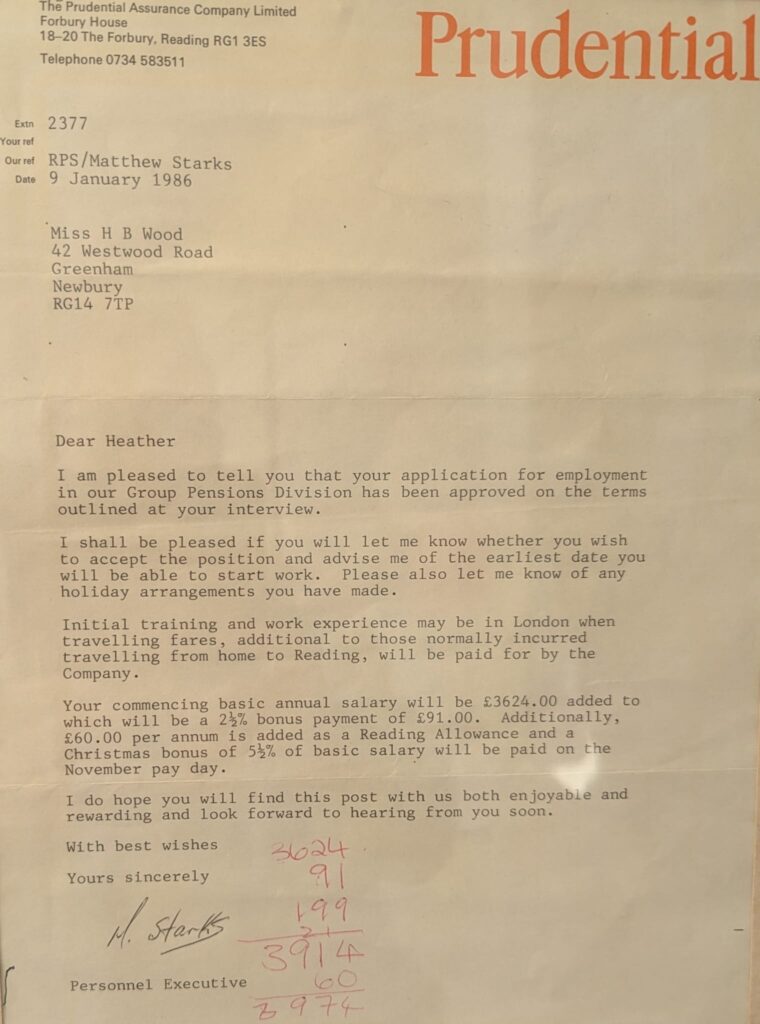

But her previous job, from 1986 (when she was 18) until 2003, including three periods of maternity leave, was at the Prudential in Reading – it’s where we met.

After she died, I found this 1986 letter offering her the job, at the princely salary of £3,624 a year, plus annual bonus, Reading Allowance, and Christmas bonus:

Another great benefit of working at the “Pru”, at that time, was being put into the non-contributory(!) DB Prudential Staff Pension Scheme (PSPS).

Here’s the homepage of the PSPS website – in the UK, the Pru is now M&G:

So, just like I receive a £24 a month RCBPF Spouses Pension, I also receive a Spouses Pension from PSPS.

This one is rather higher, given Heather’s higher earnings at the Pru, and her 17 years’ service.

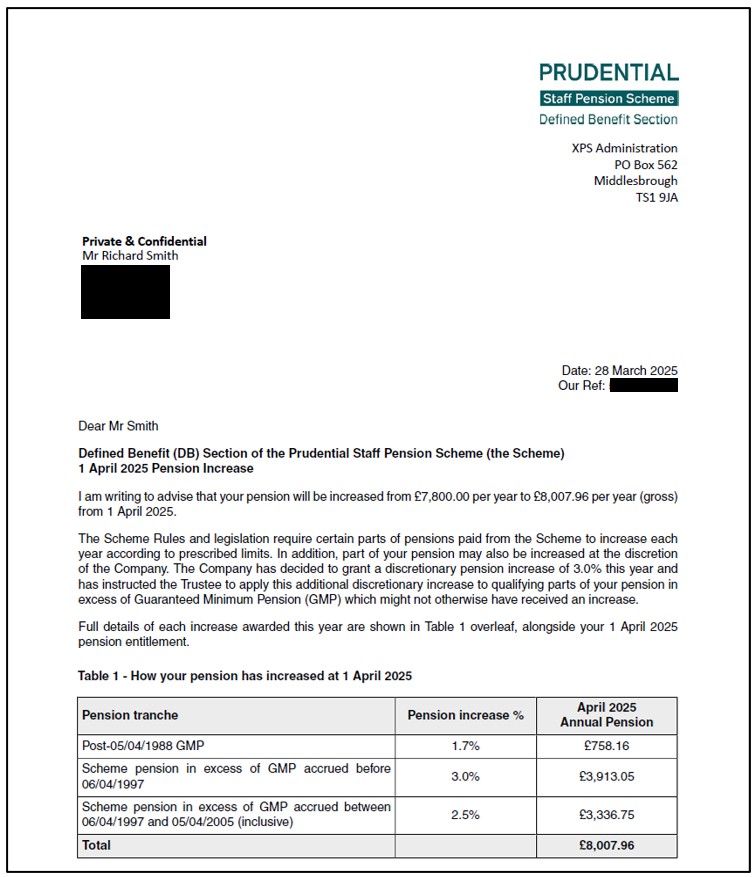

Here’s my latest PSPS Spouses Pension increase letter from March 2025 (which I can access from the member website of the PSPS administrator, XPS Group):

So my PSPS Spouses Pension is currently £8,008 a year, or about £667 a month.

It keeps pace with inflation too: when it started in 2014, it was c.£6,000 a year, so, like my RCBPF Spouses Pension, it’s also gone up by a third over a decade.

Again, I receive a PSPS pensioners newsletter, which gives a really lovely sense of community.

I am enormously grateful to the teams at both RCBPF and PSPS (and their administrator XPS Group) for paying my spouses pensions, month in, month out – it really is appreciated, especially as a single dad over the last 11 years, and into the future, until I die too.

Thank you all very much x

Building the full picture

So now we’re starting to build up a total retirement income stream:

RCBPF Spouses Pension £24 a month

PSPS Spouses Pension £667 a month

Total Spouse Pension £691 a month

In addition, you may have read Part 2 above, where I brought the first of my own pensions into payment (i.e. my PPF Compensation from Heaths in the 1980s):

Total Spouses Pen £691 a month (from above)

PPF Compensation £176 a month (from Part 2)

New Total Pension £867 a month

How much are your core bills every month? Mine are rather more than £867.

So I’m lucky I’ve also got my own PSPS pension (from my time at the Pru) and my Centrica pension (from my time at The AA) which I can bring into payment too.

I’m getting retirement quotes for these, from XPS Group and Aptia respectively. I think, in total, they might give me another £5,000 a year, or about £416 a month.

That would increase my £867 a month above to about £1,283 a month (or just shy of £15,400 a year).

Now that’s starting to look like a decent figure!

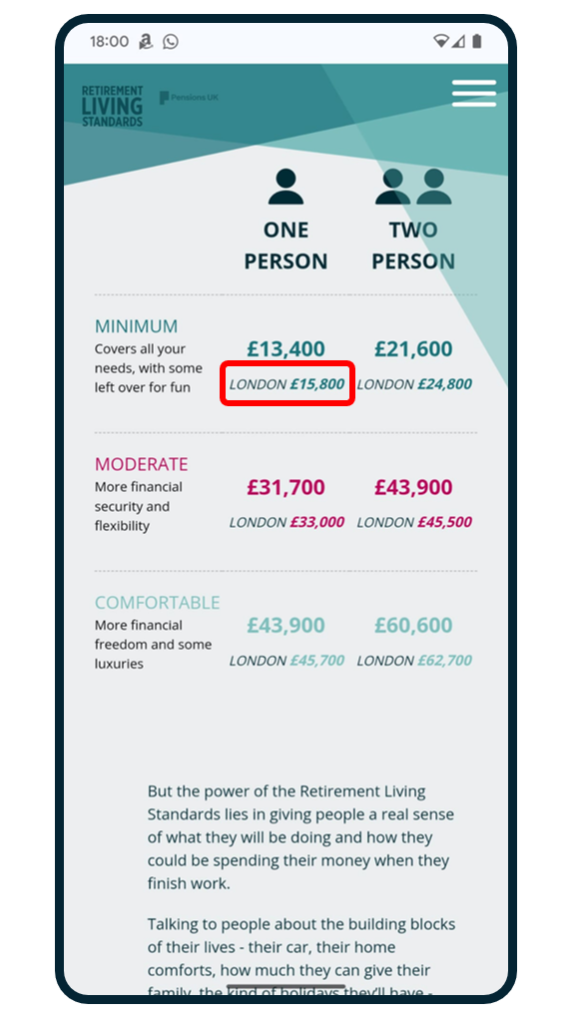

Retirement Living Standards (RLS)

So with my Spouses, PPF, Pru and Centrica pensions combined, I may receive a total pension income of about £15,400 a year. Is that enough to cover my bills?

Well, you may have heard of a pensions organisation called Pensions UK – my ear appears on the homepage of their website:

Pensions UK has developed something called the Retirement Living Standards (RLS) to help individuals picture what kind of lifestyle they could have in retirement and the costs involved.

Spookily, the Minimum income standard, for a single person like me living in or around London, is £15,800 a year, not too dissimilar to my £15,400 a year:

So it looks like my pensions in payment should, roughly, be able to cover my basic needs.

But woah, hang on a minute. There’s a very important word I’ve not mentioned yet (well, two words actually): income tax.

All my pension income figures above are gross pensions, before income tax. What I receive in my bank account each month, of course, are net pensions after income tax has been deducted.

With a Personal Allowance of £12,570, my income tax payable on my total £15,400 pension might be:

First £12,570 a year: 0% payable

Next £2,830 a year: 20% payable = £566

So my £15,400 a year gross might be reduced by £566 to about £14,834 a year net.

You may know I love maps. Here’s where I live in Wokingham:

The Minimum One Person RLS, for everywhere except London, is £13,400.

Halfway between £13,400 and £15,800 (the Minimum One Person RLS for London) is £14,600.

So, if I do receive somewhere around £14,834 a year net, I guess you could say I’m roughly halfway between London and everywhere else 🙂

Lots more to share

That’s enough for now.

What writing the above has shown me is that there’s still a lot of information to share.

My simple income tax calculation above was exactly that: simple. In reality, I will have multiple income streams, all with their own tax deductions – that’s gonna warrant a whole blog Part in itself.

Plus, I want to tell you about my experiences bringing my XPS Group-administered PSPS pension, and my Aptia-administered Centrica pension, into payment.

Do you think they’ll be as highly automated & smooth as the fully online PPF process (videoed in Part 2)?

Thanks so much for reading.

If you liked it and would like to come back for more, I’ll post on LinkedIn as usual when Part 4’s available.

Cheers for now, and thanks again to RCBPF and PSPS x

BLANK

BLANK

Part 4 – A Darlington diversion (28 September 2025)

This series of blog articles is about my retirement.

But Part 4 (and possibly 5) will take a brief diversion.

27 September 2025 was the 200th anniversary of the launch of modern railways, transforming the world.

The celebrations received much media coverage.

I’ve been watching and listening to some railway history and I travelled to County Durham for the celebrations.*

It made me reflect what lessons there might be from that successful launch of the railways in 1825 for the launch of pensions dashboards in the UK.

There’s a huge amount I could focus on, and a great deal’s been written already about the history of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR).

I’ve been thinking about the behaviours of the people who:

a) made railways happen in the first place, and then

b) made them effective.

In this context, I think there are at least three key aspects we can take from 1825:

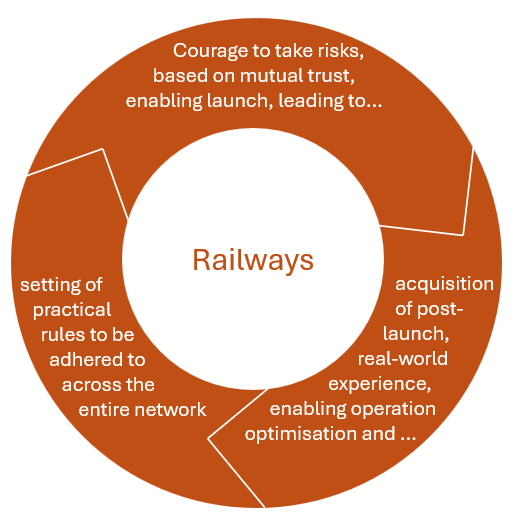

- the courage different people had to take many risks, and the trust to get railways launched

BLANK - the post-launch real-world experience which showed what they had got wrong and what needed to be rectified or enhanced

BLANK - the rules which needed to be developed in light of that experience, not before it.

Below are my brief reflections on each of these three themes, and then some thoughts about what this might mean for private sector dashboards in the UK.

BLANK

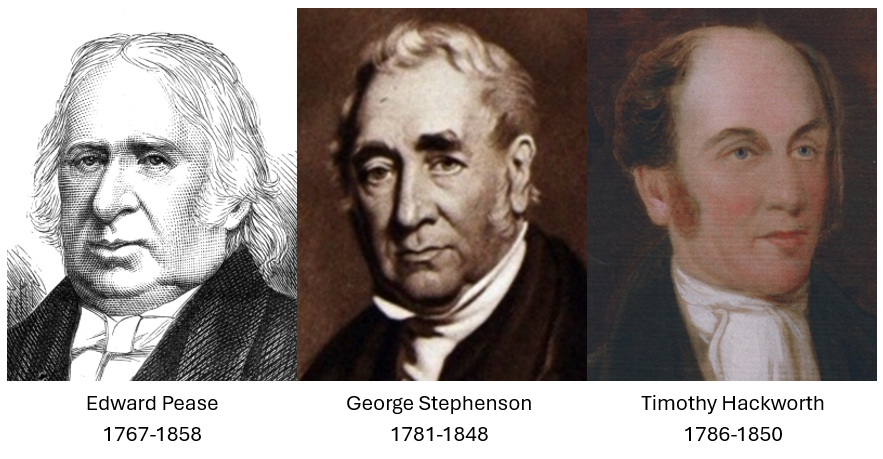

Source: Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, People Of The S&DR

Courage and trust

Learning about the inception of the S&DR, it seems to me everybody was taking risks, be they political, technical, commercial or personal. For example:

- Retired wool mill owner and merchant Edward Pease took a risk on his 19-year-old son Joseph to author the prospectus to raise investor funds for the project

BLANK - Quaker investors, like banker Jonathan Backhouse, and others, took a risk on Edward Pease to drive the project through to completion

BLANK - Edward also took a big risk on engineer George Stephenson when George persuaded him and others to make the S&DR steam-powered (as opposed to horse drawn) – George then had to replan the route to cater for steam

BLANK - George took a risk on his son Robert Stephenson, and others, to develop and deliver the locomotive power he had promised Edward

BLANK - Parliament took a risk on all involved in granting permission for the construction and operation of the S&DR (only enacting the necessary legislation on the third attempt of the promoters).

No one knew exactly how the railway would turn out.

One little illustration of this uncertainty is the name of the S&DR’s first passenger coach, which they called ‘Experiment’.

Image: Replica of ‘Experiment’ built in 2025 by Northern Heritage Engineering in Darlington

So why were so many parties willing to take such risks?

I think it was because they had both courage (in themselves) and trust (in each other).

Many of the key relationships involved were based on family (the Peases and the Stephensons, for example) and on friendship (for example through the Quaker Friends, known for their values of honesty, plain speaking and fair dealing underpinning their work).

All parties were also trying to do something good for society.

Yes they were trying to make a profit for themselves, but their wider ambition was the creation of a new transport system that would change society.

And they were willing to put up their own money (Pease included) to help that happen.

The S&DR motto, inscribed on the Experiment coach, was the Latin phrase:

“Periculum privatum utilitas public”

which translates to “At private risk for public service” or “for public good”.

This motto reflected the vision of its founders, who used their private wealth to create a public utility.

Post-launch experience

Through a huge collaborative, and trusting, effort many parties worked together to enable the S&DR to launch on 27 September 1825.

As the Guide to the Darlington Hopetown Museum puts it: “The S&DR was a triumph of collective endeavour, proving what can be done when individuals join forces and put their ingenuity and enterprise to work for the public good”.

In history, Pease has become the famous founder, investor and promoter of the scheme, and the Stephensons have become the famous civil and mechanical engineers who designed and built the line and locomotives.

Essential roles for sure. But who actually got the S&DR to work effectively?

A lesser known name is that of the S&DR Superintendent Engineer Timothy Hackworth.

Hackworth overcame the myriad of problems which arose post-launch, mitigating the inherent risks, and ensuring the railway delivered its promised benefits.

On a technical level, early locomotives were unreliable. Hackworth not only kept them running through repairs and improvements, but also designed the first locomotive (The Royal George, 1827) to withstand the rigours of everyday commercial use. It was a far superior machine, powerful and reliable enough to serve on a permanent long distance railway.

Hackworth was effective at realising commercial benefits too. When Joseph Pease commissioned a branch line extension, across the River Tees, to a small hamlet called Middlesborough Farm (with 25 inhabitants), much of the subsequent success of Middlesbrough was born out of Hackworth’s imagination and engineering prowess.

He designed the original coal loading staiths at Middlesbrough Port as well as the first locomotive (The Globe, 1830) to deliver coal to Middlesbrough.

In 2022, a giant mural commemorating Hackworth (“a true northern genius”) was unveiled in Middlesbrough:

Design flaws with the railway itself also emerged during live operations. The S&DR was built as a single track, meaning that trains would meet each other head on. Instead of one train reversing, passengers would disembark and have a fight with the occupants of the other train.

Who could possibly know that people would behave like that without that live experience?

Changing single to double track is not easily achieved. But the experience led to George Stephenson designing his next railway (the Liverpool & Manchester, opened in 1830) as a double track.

The key point is that you don’t know how things are going to work in practice until you launch. And when you do, you need effective managers like Hackworth to overcome the challenges and optimise operations.

Rules

Once the S&DR was launched, and practical live experience of operations was acquired, it became clear that various operating rules would be needed.

For me, one major point was that a whole new set of commercial rules were required.

Originally, different operators could pay the S&DR company to use the line. But this caused all sorts of operational problems, so the model was changed to the S&DR running the trains, which merchants and others could then pay to use.

Another party where rules were found to be needed was passengers – remember the original primary focus of the S&DR was freight, not people.

At first, passengers tended to open coach doors and just get off wherever they wanted to (because no one had told them not to). Clearly that wasn’t safe and rules had to be introduced on where doors could be opened.

Many other aspects required rules in light of practical experience operating the S&DR, such as luggage allowances, tickets, railway job roles, and so on.

Eventually, railways even necessitated the standardisation of time (I’ll refer to this in Part 5).

The key lesson is that it was only possible to know what rules needed to be made through the launching and live practical operation of the railway.

What does this mean for dashboards?

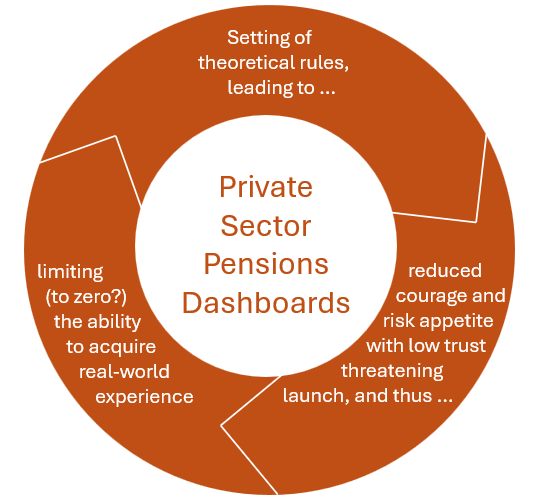

With private sector pensions dashboards (PSPDs) in the UK, instead of starting from a position of courage to take risks, and mutual trust, we’ve started at the other end.

With the Stockton & Darlington Railway (which became the template for the whole world’s railways), courage to take risks, based on mutual trust, enabled a launch to take place, followed by the acquisition of practical experience, and the consequent setting of rules:

However, with the potential 21st century network of PSPDs, we have started with theoretical rule making, which has suppressed firms’ risk appetite, in an environment where there is already low trust between industry, Government and the public. This lack of risk appetite could in turn threaten the launch of any PSPDs, meaning no practical experience can be acquired:

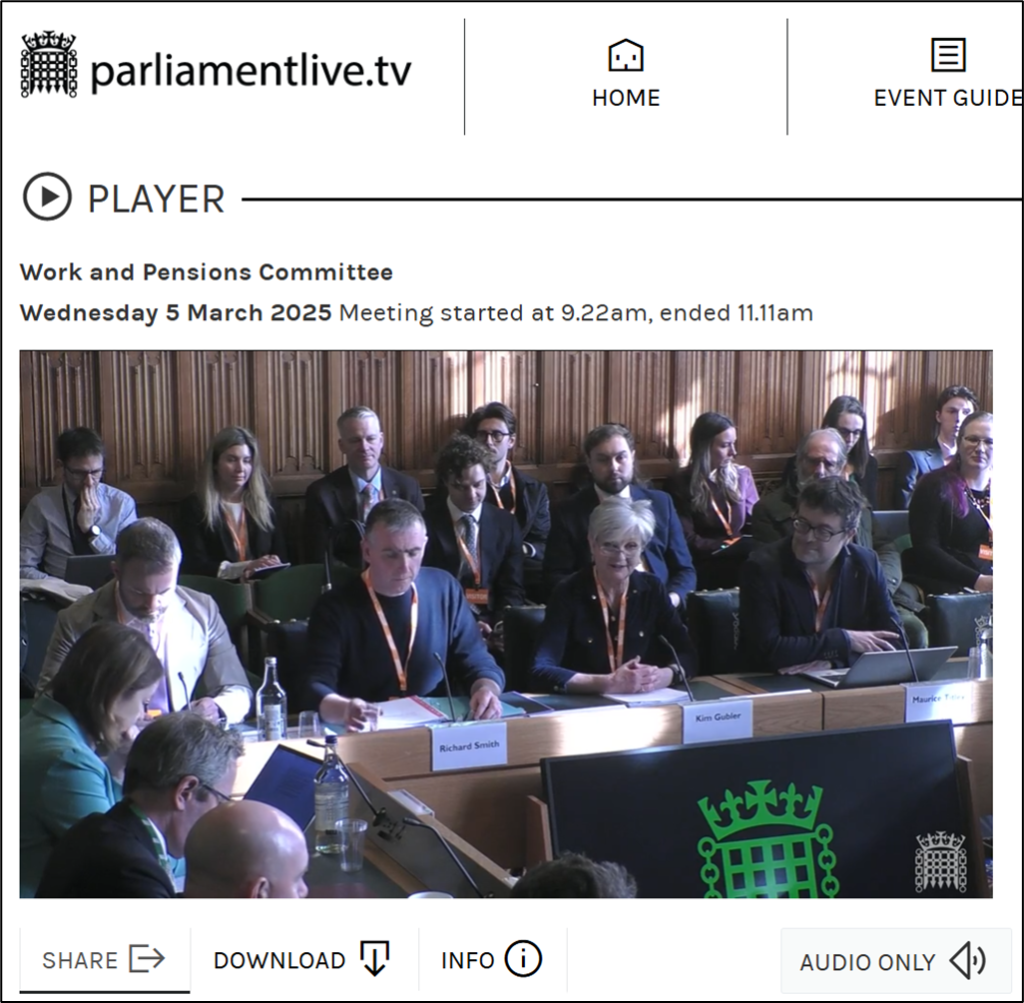

Based on a hunch, I told the Work and Pensions Committee in March 2025 that, even though it breaks my heart, I don’t think we will see any PSPDs launched.

None of my reflections this weekend (about the successful launch of railways, and the essential ingredients of courage, trust, launch and live experience before detailed rules are settled) have changed my mind.

If anything, I’m even more certain than ever that we won’t see any PSPDs.

But what do you think? I would love to be proved wrong.

If your firm has the risk appetite to allocate resources to kick off a PSPD project, it would be great to hear why – please do feel free to message me. Many thanks.

What’s next?

I’ve also been reflecting on how much railways have changed in 200 years.

So I thought I might write a Part 5 of this blog series on what some of the key aspects of that 200-year history might teach us about how dashboards could potentially develop into the far future.

* What I’ve been watching and listening to:

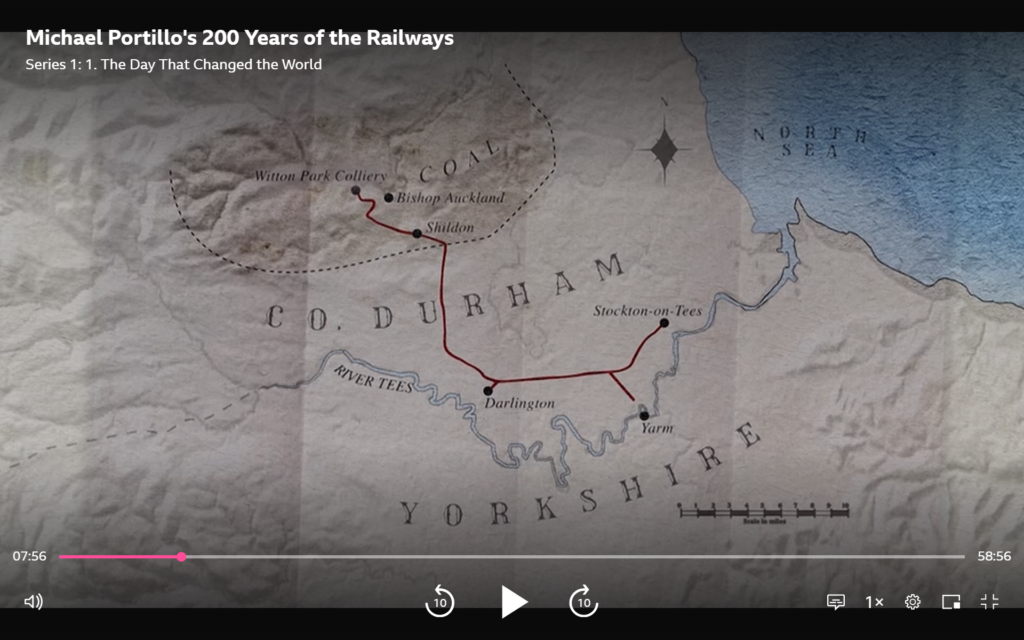

The excellent two-part BBC documentary Michael Portillo’s 200 Years of the Railways was broadcast over the last two weeks (do watch it on BBC iPlayer if you can).

On Audible, Christian Wolmar narrates his excellent book Fire and Steam, a history of how the railways transformed Britain. For the Railway 200 celebrations, Christian’s revised the book, which is coming out in paperback on 6 November 2025.

Finally, to truly get the spirit of Railway 200, I travelled to County Durham to witness first hand the recreation of the first ever steam-powered passenger railway journey anywhere in the world in September 1825:

BLANK

BLANK

Part 5 – Two centuries of parallels (coming in January 2026)

This series of blog articles is about my real experience of gradually moving from work to retirement, and bringing some of my pensions into payment over time.

But Part 5 (like Part 4 before it) takes a brief diversion.

Throughout 2025, Railway 200 celebrated 200 years since the birth of modern railways.

For Part 4 above, I travelled to the Stockton & Darlington Railway to witness the celebrations.

Two BBC News reports:

Above – Locomotion No 1 at Heighington (26.09.25)

Below – Double-decker Eurostar at St Pancras (22.10.25)

Over three months now since I was in the North East, I’ve been thinking about how much railways have changed over two centuries.

So Part 5 of this blog is a reflection on some of the key themes of that 200-year history, and on the extent to which those themes have parallels for how UK pensions dashboards could potentially develop in the future.

There’ve been such radical developments of railways since 1825 that I could go in various different directions.

But three themes I keep coming back to are:

- consumers: consistent, yet ever changing, needs

- change: built upon, yet constrained by, legacy

- control: neither private nor public being optimal

I’ll consider each theme in turn, including potential parallels for dashboards.

Consistent yet changing consumer needs

Looking at the two pictures above, I was struck how they are both very different, yet very much the same.

To be completed in January 2026.